An alternative vision

The weather worldwide is becoming more extreme. The last decade has brought extremely dry seasons, highlighting the vulnerability to drought of agriculture, water supplies, and urban areas and giving the topic of water a new urgency.

A look at Mexico, with its unique climate divided into distinct rainy and dry seasons, complex urban-rural dynamic, and intricate political and social interdependencies, provides valuable insights into adaptation and coping strategies.

Reserva el Peñón is a pioneer of resilient design in Valle de Bravo, Mexico, and uses innovative approaches to tackle water-related challenges. The project is in a natural protected area approximately 100 miles from Mexico City. The area is part of the infrastructure of the megacity: the regional basin collects water and pumps it to the city’s 22 million inhabitants.

Spanning 450 acres, Reserva el Peñón sits on a slope covered by rainforest and pine and oak forest. There are two towering volcanic rocks. The site was formerly used as pasture land for “milpa” agriculture, a traditional system in which maize is intercropped with beans, squash, potatoes, or other species. Milpa has been a sustainable method of growing crops—and for the extraction of firewood–for millennia.

The region has faced decades of pressure from mining, irregular settlements, and illegal logging. Its natural beauty makes it attractive to real estate developers, and the site’s owners had plans for a resort with a golf course and five hundred country homes. Recognizing the danger that traditional development posed to this rain forest, I collaborated with colleagues to create an alternative.

An initial site analysis revealed lack of access to water and the damaged condition of this pristine territory. Could a sustainable, collective-driven community design be both feasible and attractive to investors?

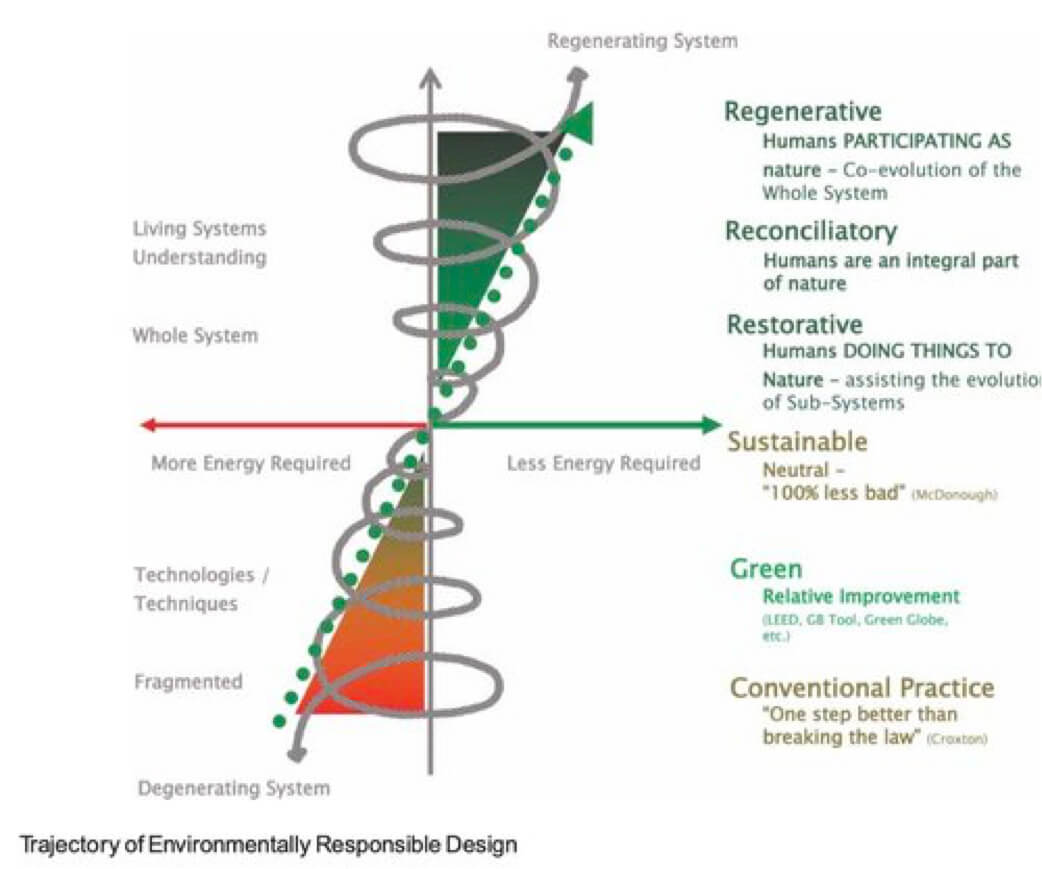

Two sources of inspiration were crucial for our team. One was Bill Reed’s ideas from his article “Shifting from ‘sustainability’ to regeneration,” published in 2007. The second was permaculture´s keyline design.

Regeneration through design

Bill Reed argues that sustainability is about doing less damage to the environment, and “it is necessary to learn how one can participate with the environment by using the health of ecological systems as a basis for design. The role of designers and stakeholders is to create a whole system of mutually beneficial relationships…By doing so, the potential for green design moves beyond sustaining the environment to one that can regenerate its health.”

In the case of Reserva el Peñón, the result is a water-autonomous country house settlement that addresses the community’s water needs without relying on external freshwater sources or wastewater connections.

The planning and design are based on keyline technology for pasture farming, developed in the 1950s by P.A. Yeomans in Australia. The aim is increasing resistance to dryness, erosion, and flooding, as well as storing rainwater and improving soil fertility.

In keyline design, the climate specifies the rules of the game; the topography, with the associated natural behavior of water, is the game board. The system begins with climate, terrain, and geology, which can only be influenced to a small extent by humans. Planning then turns to hydrology, access routes, parceling, soil formation, flora, and fauna. The process reverses the approach that is usually used in urban planning.

Water management is guided by the principle of “slow it down, spread it out, and sink it in.” Through 15 interconnected dams and a decentralized network of reservoirs along the keylines–the natural paths of water–the site is divided into multiple water catchment areas. Six miles of hedges separate eighty private plots. Gravity ensures that higher elevation reservoirs supply approximately 35 percent of household water needs. Rainwater collected from rooftops and stored in cisterns by each household supplies the remaining 65 percent.

The soil is slowly regenerated, enriched with water to promote water storing vegetation. Roads and paths follow contour lines and are lined with native trees, shrubs, and plants, which offer protection, habitat, and food for local and migratory birds and fauna. With minimal maintenance and no irrigation, the landscape delivers medicinal teas, berries, fruits, and firewood.

Beyond the technical aspects, Bill Reed’s concept of “the story of place” is vital. By connecting the dots through a narrative, individuals understand their role in nature and their agency in preserving it.

Through a governance structure focused on learning, the community engages in workshops that foster emotional connections and facilitate learning from nature. Over 30 workshops were held last year, ranging from woodworking to mushroom foraging to local wildlife identification. These activities instill a deep sense of caring, appreciation, and connectedness. Kids in particular are transformed by these experiences.

Innovative design remains crucial as we address the impacts of climate change in local weather, ecosystem health, and water supplies. The urgency surrounding water-related challenges is felt worldwide. Conserving and improving water quality has the potential to significantly enhance the health and sustainability of built environments in Mexico and beyond.