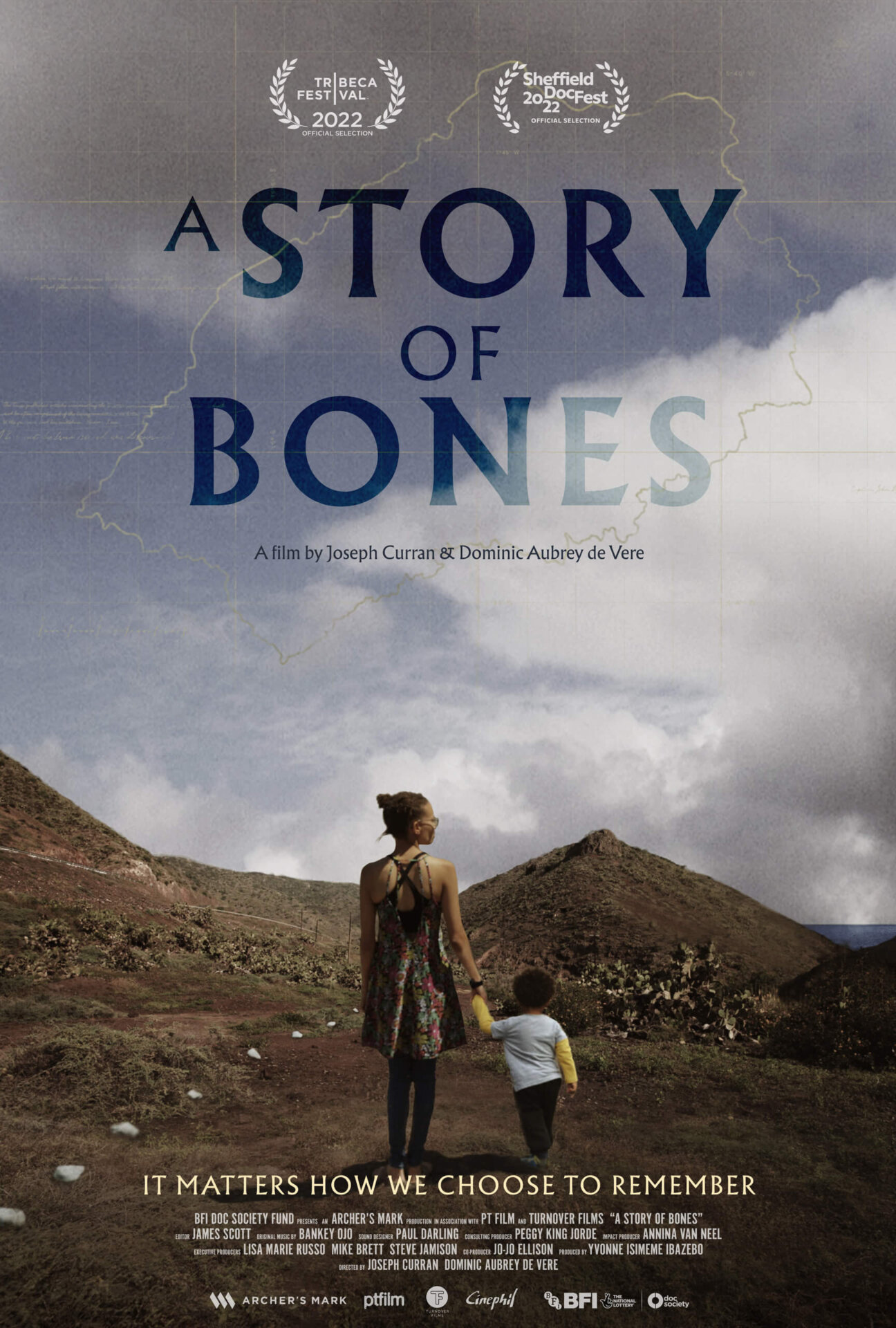

A Story of Bones is a 90-minute British documentary and a call to action for change. In addition to screenings for members of the British Parliament and Africa’s prominent Zanzibar International Film Festival, it had its US television premiere on PBS’s Point of View last July.

.

Contributing to a feature length documentary is new for me, and I’ve discovered the incredible opportunities for building impact for the issues important to my work in preservation. I am the consulting producer, impact producer, and protagonist in A Story of Bones, and since the world premiere at the 2022 Tribeca Film Festival in New York City, the reception to the film has been overwhelming. To highlight a few, we’ve presented at the London Barbican and Conduit venues and human rights film festivals in Berlin, the Hague, and the US.

The story unfolds on the British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, a tiny remote island in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean, home to just under 5000 people. Most famous as Napoleon’s place of exile after being defeated at Waterloo, the island still hosts Bonaparte’s empty grave – a symbol of Britain’s former Empire and colonial past. When the rapid construction of an airport access road resulted in the desecration of a massive burial ground for 10,000 enslaved Africans, it caught the attention of two young British documentary filmmakers, Joseph Curran, and Dominic de Vere. They had come to the island to document a different story. Still, as they learned more about the hidden history around the so-called “Liberated African Burial Ground,” their film project took a new direction.

In 2008 the UK government ordered the excavation of 325 articulated human remains to make way for the airport access road. The unmarked graves were host to thousands of enslaved Africans who died en route to the Americas between 1840 and the 1860s and were retrieved from the hulls of slave ships. The remains were exhumed, placed in boxes, and moved into a storage room in the wing of the island’s prison facility. Records reveal that many victims of slavery were from the Congo. Artifacts were exported to Liverpool for research purposes for approximately ten years before returning to St. Helena. Unfortunately, extracting cultural resources from a community to conduct research, interpret, and produce publications with little or no meaningful engagement or consent by the descendant community is a practice that continues to marginalize descendant voices from the dominant historical narratives. The treatment of St. Helena’s African Burial Ground is not unique.

The film’s arc centers on Namibian ex-pat Annina van Neel, who arrived four years later in St. Helena as the airport project’s chief environmental officer. Annina was tasked with handling any additional human remains unearthed during construction, but over time she faced increasing resistance and cultural indifference to respecting the burial ground. She eventually found an ally and mentor in me. For more than a year, we communicated by email and Skype, collaborating on strategies to preserve and memorialize a burial ground recognized as the most significant trace of the Transatlantic slave trade and the Middle Passage.

My work on the New York African Burial Ground was born of a similar struggle 30 years earlier. The burial site gained significant international attention, and I served at the helm to implement plans for honoring the memory of thousands of enslaved and free Africans buried in Lower Manhattan. It ignited a grassroots movement to reclaim African burial grounds in the US and abroad. The lessons we learned were transformative and have informed my practice.

After returning from St. Helena, I organized a US tour for Annina to visit the New York African Burial Ground and meet critical stakeholders pivotal to the site’s preservation. The tour culminated in a road trip through the American South, including stops in Montgomery, Alabama; Atlanta, Savannah, and my native Albany in Georgia; St. Helena and Charleston in South Carolina. We visited the tangible reminders of the slave economy directly tied to the American South and Britain. The journey would help contextualize global narratives around slavery beyond the insular and geographical boundaries of St. Helena.

Annina returned to the island with a renewed vision, inspired by our plan to join forces in a global campaign building awareness of the burial site. Stateside, I was well positioned to conduct outreach and increase impact in several ways. In 2019 MP David Lammy and MP Diane Abbott accepted my request to meet in their London offices to solicit support. I used my platform as a keynote speaker at a United Nations Slavery Remembrance event and advanced media outreach. The documentary, once completed, would be a vital tool for our impact campaign.

Still, we had not anticipated that the New York premiere of A Story of Bones would prompt Island leadership to expedite the reburial after 14 years in storage, however without significant participation by the African diaspora and without observing ceremonial rites or rituals. The ceremony was inconsistent with the approved master plan that Annina and I helped develop. The coffins were placed in a mass grave adjacent to a fuel yard; the burial ground remains unprotected and without a world class memorial honoring the thousands of victims of the Transatlantic slave trade. Meanwhile, the empty tomb of Napoleon Bonaparte– the man who reinstated slavery–is celebrated and funded as the island’s main attraction.