By initially looking at the overall problems–not just the technical challenge–many chances may be identified to address the urban realm, social and inequality issues, biodiversity and climate change, and health and wellbeing deficits at virtually no extra cost.

Over the last couple of years I have worked on transport infrastructure schemes outside the UK where it was clear that the transport issues were not the only problems. Poor quality urban realm, lack of connectivity and pedestrian and cycle access, and social division and inequality were all patently evident. So were environmental degradation, lack of biodiversity, and predominance of hard surfaces contributing to heat-island effect and surface water run off, but the opportunities were also obvious. Throughout the design process, every opportunity was taken to introduce physical and social measures that were sustainably integrated into the wider urban fabric and that contributed positively to climate change mitigation and social wellbeing.

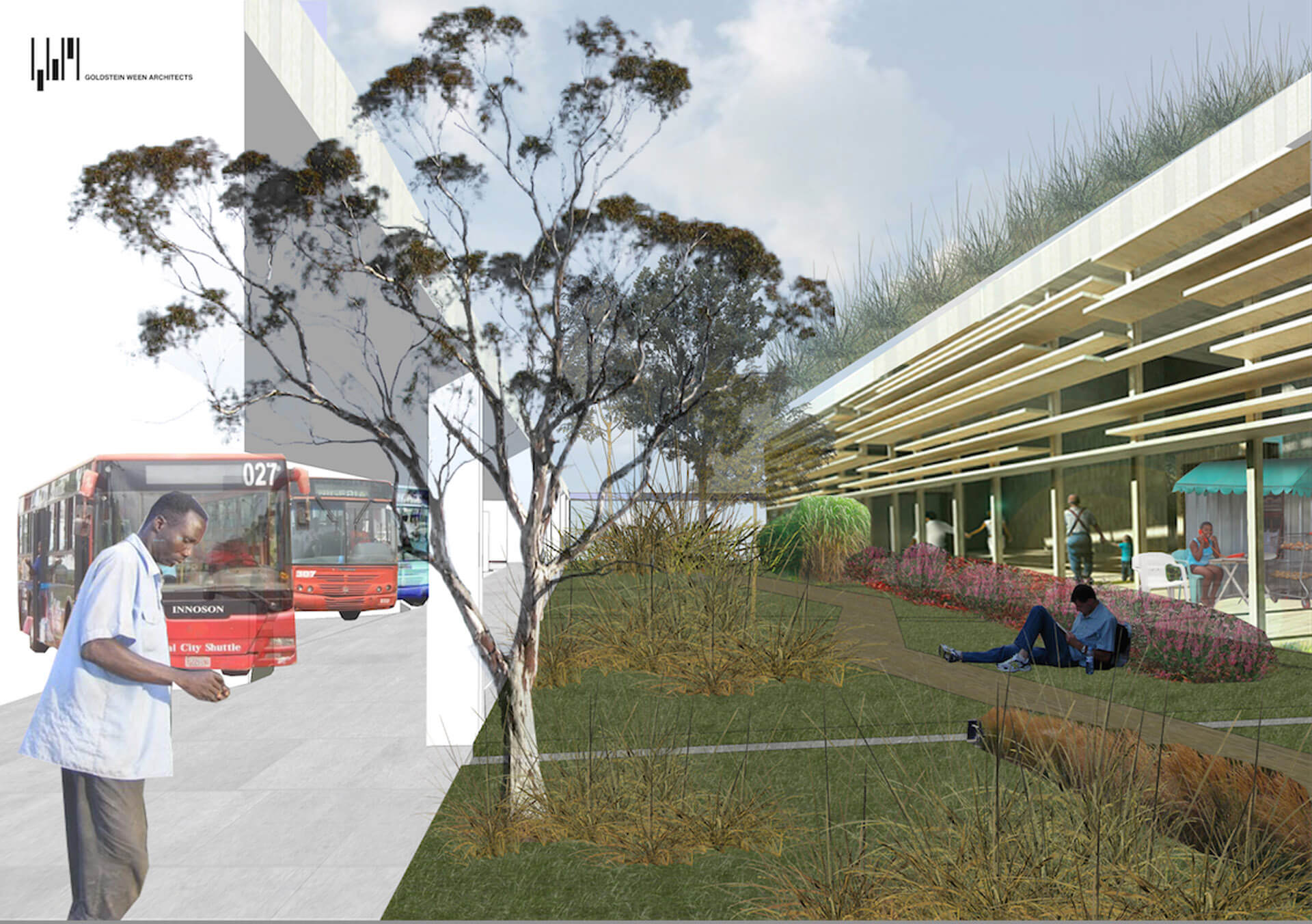

Kano Freight and Bus Hubs

A project in Kano, Nigeria, for the World Bank Environment Program, in collaboration with Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN and IRIS Consultancy and Logistics, was charged with providing 3 freight terminals and 3 bus interchanges within the city. The sites were located in areas dominated by traffic and unplanned development and had the characteristics of “islands.” The city as a whole is largely devoid of any biodiversity and suffers from lack of green infrastructure.

The brief focussed on the obvious issues of location and function with little reference to sustainability and environmental issues, despite the funding from the World Bank Environment Program. Yet traffic congestion is a major problem and the pedestrian and cycle environment is very poor. Street crossings were nonexistent, and there was virtually no shade or protection.

Our emphasis was on stitching the sites into the wider city and ensuring permeability in the long term. We created obvious walk and cycle routes through the sites, prioritizing desire lines over traffic and separating busses from pedestrian traffic. To provide a combination of active and calm areas for passengers, who often have long waits for bus connections, the fronts of the bus stations on the main road have zones for trading stalls and cafes.

The freight parks had similar overriding concepts: integration, permeability, and maintenance of continuous walk and cycle links. Instead of vast seas of tarmac, truck parking was arranged in back-to-back rows separated by wide landscaped strips with seating and picnic tables as rest facilities for the drivers. At the ends of each strip were toilets and showers, as well as cycle hire facilities, so that drivers can access the center of the city easily. As with the bus stations, the green strips are through-routes for pedestrians and biodiversity corridors.

Health and lifestyle was behind both design concepts. Trees in the new facilities contribute to improving the air quality. Also, the cycle friendly facilities promote healthier and more active lifestyles and reduce reliance on car and motorcycle travel. Ultimately, it is hoped that an overall municipal development strategy would aim to link green spaces and create a legible and convenient network of walking and cycling routes, so that more of the city will have better air quality and richer biodiversity.

Mexico City Transport Interchange

I was invited by Urban Travel Logistics, Mexico, to look at a project in Mexico City that had a single focus: to create interchange between a suburban commuter rail station and two Bus Rapid Transit routes. It was immediately evident that there were much wider issues at play. One side of the railway was highly affluent, with all the amenities of a wealthy neighborhood, whereas the other side was a large informal settlement rising up the slopes, with little or no infrastructure of any kind. Adjacent to the rail station but with no adjacent entrance was a regional hospital, thereby rendered accessible only by car. Further, a local park was severed from everything by highways.

Transit from the BRT stops to the station on one side was very difficult and on the other side virtually impossible. One involved passengers having to cross a 6 lane urban motorway; an over bridge did exist, but it was so far off that no one used it, and instead people ran the gauntlet of fast moving traffic. Fatal accidents are commonplace. The BRT line on the other side of the railway landed in the middle of a highway, and access to the railway involved a long unattractive walk along a ramped and elevated caged walkway.

The inequality between the two communities was clearly a fundamental issue. The informal community was detached from opportunity, the healthcare facility, the urban park, or any of the amenities of the more affluent neighbourhood. Fixing the interchange between the BRT and rail was easy enough, but by putting the social problems into the mix, it was possible to address all the issues at once. The solution was a permanent link shared by cycles and pedestrians across the railway and highways, connecting the two communities, the station, the BRT stops, the hospital and the park.

Cycle access, cycle parking, and links to wider cycle routes promote active travel in a car-dominated city that suffers from obesity and high levels of air pollution. The link was a first step towards establishing social equity. The additional attributes were added to the project at insignificant extra cost.

Medellin Public Transport Cable Car

A much more ambitious infrastructure project is the cable car public transport link that was introduced in the city of Medellin, Colombia, in 2004. It is an exemplary case of using public transport projects to heal disrupted communities. This pragmatic solution, overseen by Alejandro Echeverri (LF ’16), who was the city’s director of Urban Projects, provides public transport to informal settlements on the very steep hills above the city, where most traditional solutions would have been invasive and difficult to engineer. The network of cable car lines is fully integrated into the city’s public transport system and was relatively quick and easy to install. Metrocable provides 10-15 minutes access to opportunity and work for thousands of residents who previously commuted up to 2 hours to the city center.

Notably, the municipality chose to engage local inhabitants in the planning process. Years of social unrest and gang warfare meant the valleys between the communities were virtual no-go zones. The community participation process identified key priorities over and above the need to reach jobs: social cohesion, access to education and culture, and community integration.

Physical bridges now link across the canyons, so the communities are better connected and integrated. As a result of the participation process, the residents are proud of their community, and insist on showing visitors what has been created.

All these strategies demonstrate that it is possible to broaden the scope of a project by looking at the local issues and identifying opportunities to solve them at little or no extra cost. Adopting this approach would ensure that we maximize the benefits of investment in our infrastructure. Things that improve society and our environment are fundamental to creating the liveable sustainable city. It should be a priority, therefore, that we take the opportunity to address wider societal and environmental deficiencies, especially when it is so difficult to raise funds for these small interventions as stand-alone projects.

The reality is that once infrastructure projects have been delivered, they are rarely revisited within a lifetime. When I hear excuses like “mission creep” I ask, “can you afford to miss an opportunity that may not arise again for a very long time?”