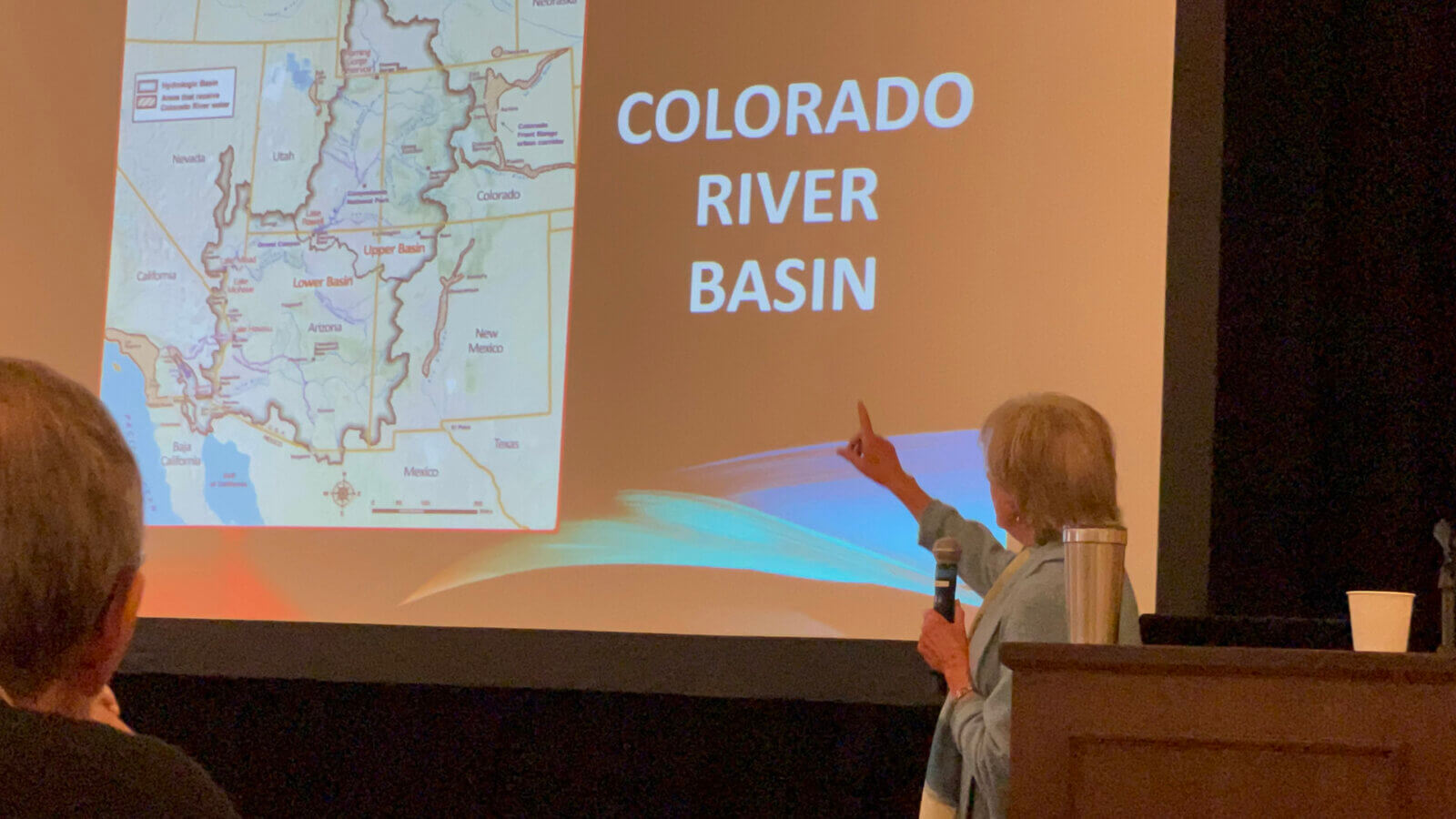

“Mighty” is the word. The Colorado River runs through four states, with a watershed encompassing parts of seven US states and two Mexican states. It provides water for 40 million people–including 30 Native American tribes that lived here long before the white man came–and supports much of the country’s food supply thanks to the agriculture in the fertile valleys of California. It is the motor of a 1.4 trillion dollar economy. But even a river as mighty as the Colorado can dwindle under the pressure of climate change and the multitude of “straws” sucking it dry.

“Mighty” is the word. The Colorado River runs through four states, with a watershed encompassing parts of seven US states and two Mexican states. It provides water for 40 million people–including 30 Native American tribes that lived here long before the white man came–and supports much of the country’s food supply thanks to the agriculture in the fertile valleys of California. It is the motor of a 1.4 trillion dollar economy. But even a river as mighty as the Colorado can dwindle under the pressure of climate change and the multitude of “straws” sucking it dry.

Water in the West is one of the themes of the Loeb Fall Study Tour 2023 to Denver, Colorado. We learn about the big issues of the Colorado River, the role of Cherry Creek in Denver’s urban planning and, on a more local level, the role of the South Platte River. Good to know: half of Denver’s water comes from the Colorado River.

Peter Pollock ’98 kicks off the plenary session with the acknowledgement that “we recognize that we are on unceded territory of the Ute and Arapaho nations.” Here in the arid West, he says, where the population is growing but the aridity is too, “water is now top of mind in city planning.” Journalist Allen Best, however, points out that 70 percent of the water is used for agriculture and a mere 7 percent is used in the cities. “Manual labor has been replaced by high capacity pumps that deplete the aquifer while making it possible to increase the amount of arable land. Farms are now as big as 30,000 acres while the towns are depopulating.” The state of Colorado, therefore, has authorized a grant of 30 million dollars to help take 25,000 acres of land out of production by 2030. Why, Best asks rhetorically, are we tapping the Ogallala aquifer to grow corn to feed cattle and to make ethanol for export?

As an example of a urban area that is stepping up to the plate, Best mentions the towns of Castle Rock, which as of this year prohibits the planning of non-native bluegrass in front yards, and Aurora, which is not permitting any new golf courses.

Anne Castle, supervisor at the Upper Colorado River Commission, gives some examples of popular sentiment around the water crisis, with people calling to “turn off the fountains in Las Vegas!” and “stop irrigating the Phoenix golf courses!” She walks us through the contentious history of the distribution of the Colorado River water, from the 1922 Compact, to that of 1948, to the emergency measures by the federal government this year, which stepped in when the states could not reach an agreement. (They have now announced that they will develop their own alternatives for 2026).

Anne Castle, supervisor at the Upper Colorado River Commission, gives some examples of popular sentiment around the water crisis, with people calling to “turn off the fountains in Las Vegas!” and “stop irrigating the Phoenix golf courses!” She walks us through the contentious history of the distribution of the Colorado River water, from the 1922 Compact, to that of 1948, to the emergency measures by the federal government this year, which stepped in when the states could not reach an agreement. (They have now announced that they will develop their own alternatives for 2026).

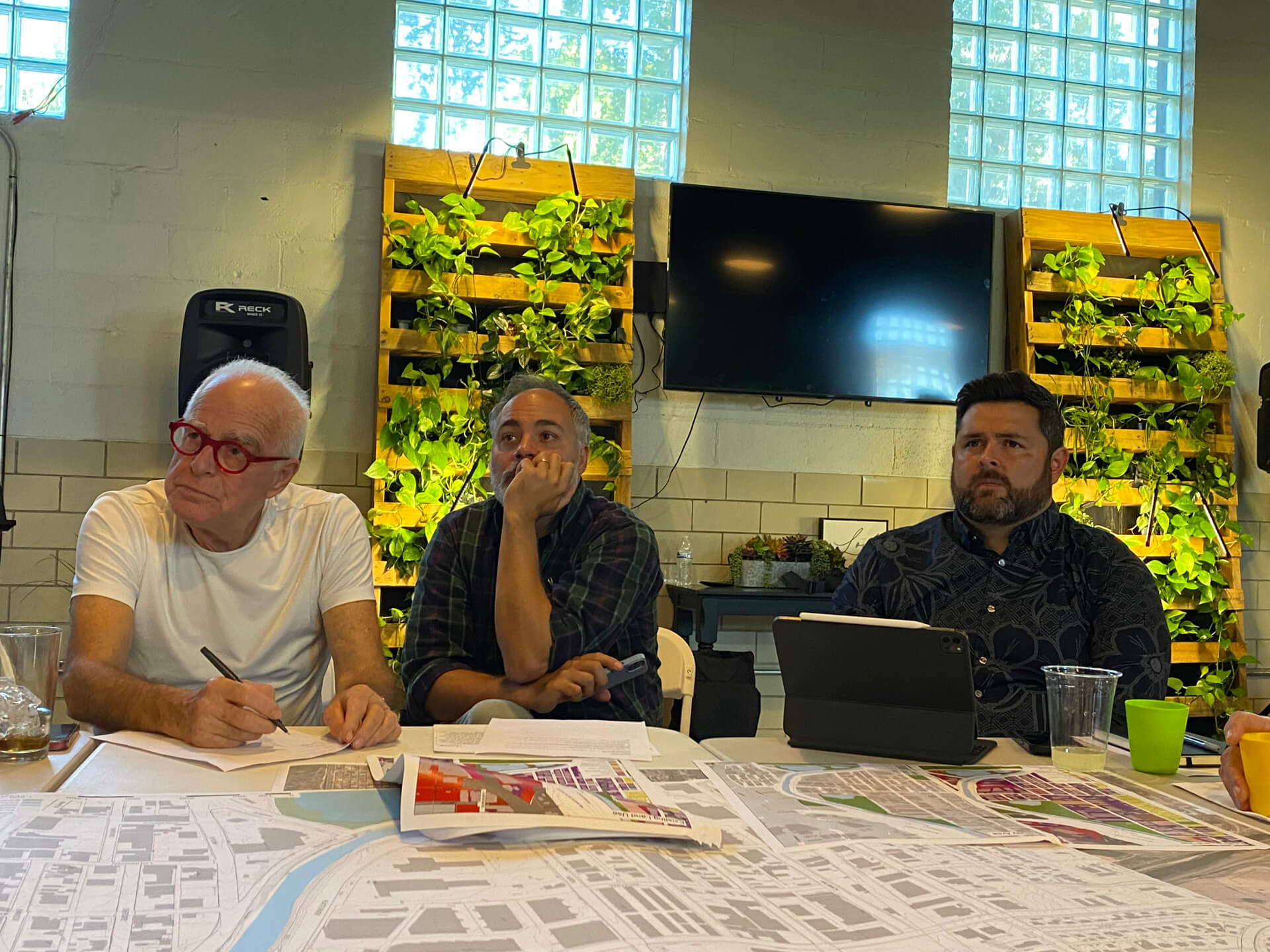

An adolescent city with an old soul. That’s how Peter Park ’12, former planning director of Denver, describes Denver at the afternoon session on redesigning the downtown, held at the office of Tryba Architects. Behind him is an image of the “birth” of Denver during the 1859 goldrush, with teepees and covered wagons at the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek – where Indigenous peoples had already lived for thousands of years. Denver once had 300 miles of streetcar tracks and walkable neighborhoods – now there are just 118 miles of rail, seas of surface parking for 41,000 cars, and lots of wide roads with isolated pockets of buildings. Peter describes the waterways frankly as “open sewers.” He says, “In the early 20th century, Mayor Speer was an advocate of the ‘City Beautiful’ movement, but he neglected the river.” The city’s relationship with water has always been awkward.

An adolescent city with an old soul. That’s how Peter Park ’12, former planning director of Denver, describes Denver at the afternoon session on redesigning the downtown, held at the office of Tryba Architects. Behind him is an image of the “birth” of Denver during the 1859 goldrush, with teepees and covered wagons at the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek – where Indigenous peoples had already lived for thousands of years. Denver once had 300 miles of streetcar tracks and walkable neighborhoods – now there are just 118 miles of rail, seas of surface parking for 41,000 cars, and lots of wide roads with isolated pockets of buildings. Peter describes the waterways frankly as “open sewers.” He says, “In the early 20th century, Mayor Speer was an advocate of the ‘City Beautiful’ movement, but he neglected the river.” The city’s relationship with water has always been awkward. We have landed here because the city will soon revisit the neighborhood plan, and so some disruptive Loeb brainstorming is welcome. This area also epitomizes a host of conditions that are typical for riverine corridors in Denver and other cities: ahighly channelized river reach is crowded by mid-century highway infrastructure that is immediately adjacent to a vitally important industrial area. One of the big questions, according to Jessica Stevens and Matthew Bossler of the city, is how to connect the industrial and residential to the water’s edge. One guest, urban designer Tom Klein of the landscape firm Wenk Associates, cycles by Vanderbilt Park daily–“the park is beautiful but I never see anyone using it.” The city has yet to do a needs assessment in these areas, and the suggestion is that they should: “Then local residents will own the park rather than feeling like they are being told what to do.”

We have landed here because the city will soon revisit the neighborhood plan, and so some disruptive Loeb brainstorming is welcome. This area also epitomizes a host of conditions that are typical for riverine corridors in Denver and other cities: ahighly channelized river reach is crowded by mid-century highway infrastructure that is immediately adjacent to a vitally important industrial area. One of the big questions, according to Jessica Stevens and Matthew Bossler of the city, is how to connect the industrial and residential to the water’s edge. One guest, urban designer Tom Klein of the landscape firm Wenk Associates, cycles by Vanderbilt Park daily–“the park is beautiful but I never see anyone using it.” The city has yet to do a needs assessment in these areas, and the suggestion is that they should: “Then local residents will own the park rather than feeling like they are being told what to do.”